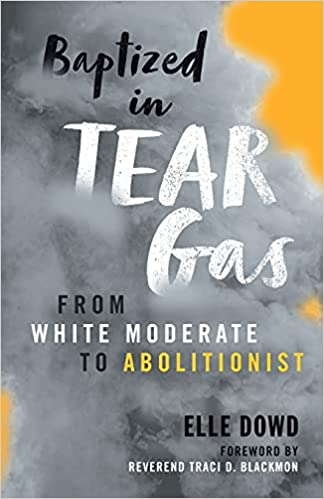

I’ve been reading Elle Dowd’s powerful book, Baptized in Tear Gas: From White Moderate to Abolitionist, in preparation for her visit to my campus ministry in a couple of weeks. In her chapter called “Joy as Resistance” she describes her arrest when she participated in a nonviolent direct action in response to the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson. It’s chilling stuff. Then I read this sentence: “They had us line up in another hallway, and again, I was with people who I didn’t know. They kept separating us and moving us around, never telling us where we were going.” (p. 116) I started to feel on edge, in that way when a connection is beginning to get made, but doesn’t yet flow. Then, a few paragraphs later:

If I was treated this way, with all of the privilege I possessed, with all eyes on Ferguson watching, how do you think young Black people are treated when no members of the media are present to tell the story? My mountains of privilege surrounded me with a cocoon of safety, and still I was beaten by police in the middle of the day with cameras watching. But Black people fare much worse at the hands of the police. They are threatened. They are terrorized. They are beaten. They are imprisoned. They are disappeared—or worse.

Baptized in Tear Gas, p. 117, emphasis is the author’s

I don’t know what sounds these kinds of connections make: Pop? Click? Whoosh? Oh, f*ck? Whatever that is, I heard it. Elle’s description of being disoriented and isolated after her arrest, the fear that no one would know where she was, of not knowing what would happen next or whether her rights or her person would be respected or violated—all of this reminded me of the myriad stories of those who stood against the dictatorships throughout Latin America. That was where I learned the use of the word “disappeared” as a noun and of “disappear” as a transitive verb with subject and object (as in “Maria was disappeared.”)

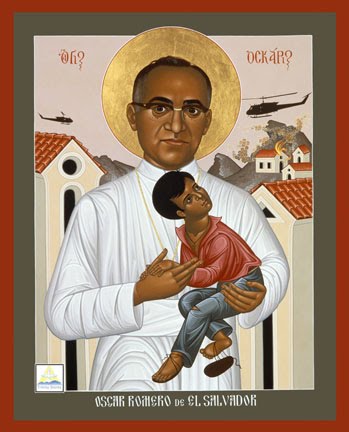

Then, in reading the second paragraph, where Elle notes that even her privilege as a white person didn’t protect her, I remembered what day today is. It is the feast day of St. Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of El Salvador, who was killed in the middle of saying Mass on March 24, 1980. It’s a day that my children and I note every year because of the ways in which it connects to our family history. Their father, who is from El Salvador, was at the Archbishop’s funeral in San Salvador when snipers began shooting at the peaceful crowd. He was tortured* by the miltary and eventually had to flee the country, fearing for his life and the safety of his family. I have other friends who had similar experiences, whose ability to live full, healthy lives has been hindered by the violence they witnessed and which was inflicted on them. El Salvador is a nation living with individual and communal trauma in ways that we (white folks, at least) cannot imagine. And El Salvador is only one of a number of countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean with a similar history of violence, injustice, and oppression—often supported by the United States.

So as I read Elle’s words, I realized (later than I should, but I am congenitally naïve) that our country is closer than I would like to believe to the kind of place I witnessed and heard about in the 80’s, a place where peaceful protest could be considered a capital crime, where police are militarized, and a place where the idol of “security”—as defined by the same military and police and others in power—demands sacrifice from those who might disrupt it or question it.

I was listening to an interview with Guillermo and María Hilda González, who were friends of Romero. María Hilda said something that caught my ear. She was describing her thoughts when she heard of Romero’s assassination: “It can’t be, if the bishop was killed, what’s going to happen to us?” If an Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Church, a representative of arguably one of the most powerful institutions in the world, isn’t safe from out and out murder, what, indeed, will happen to the poor? If four white American missionary women could be disappeared, raped, and killed, what will happen to those who can’t leave? If six Jesuit priests and the women who cared for them can be rounded up and shot in the middle of the night in their own home, will we finally step up and speak?

All of those assassinations happened in the 1980’s in El Salvador, yet the civil war didn’t officially end until New Year’s 1992. And El Salvador is still struggling to heal; the toxic, repeating cycles of violence have just shifted to other actors. Here in the U.S., we have our own martyrs. We try to sanitize them: I have been shocked (again, I shouldn’t have been, remember I am wired to be naïve) by the number of people in my social media feed who argue that Martin Luther King, Jr. would not have approved of the protests after Michael Brown’s killing, or Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, or Tamir Rice, or Breonna Taylor, or that Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the National Anthem was inappropriate. We have our own disappeared—Black men lost in the prison system, Indigenous women, trans women of color, immigrants trafficked in domestic service, agriculture, sweatshop and factory work, restaurant and hotel work and in the sex industry.

The one thing I do every year on this day is listen to the recording of Romero’s last radio homily, the sermon that probably sealed his fate. Even if you don’t understand Spanish, the authority of his words is powerful. They bring me to tears, every single time.

One of the questions that has been a theme of my ordained ministry has been that of authority. What is my authority as a priest, exactly? Is it earned or is it conferred—or both? How do I embody it and enact it in ways that promote the Gospel and encourage God’s people? Romero’s voice in his last radio sermon is an example of someone who had, it seems, answered those questions for himself. Listen to this recording. Even if you don’t understand Spanish, you know that he is speaking with God’s own authority:

I would like to make an appeal especially to the men of the army, and concretely to the National Guard, the police, and the troops. Brothers, you are of part of our own people. You are killing your own brother and sister campesinos, and against any order a man may give to kill, God’s law must prevail: «You shall not kill!» (Ex 20:13). No soldier is obliged to obey an order against the law of God. No one has to observe an immoral law. It is time now for you to reclaim your conscience and to obey your conscience rather than the command to sin. The church defends the rights of God, the law of God, and the dignity of the human person and therefore cannot remain silent before such great abominations. We want the government to understand well that the reforms are worth nothing if they are stained with so much blood. In the name of God, then, and in the name of this suffering people, whose laments rise up each day more tumultuously toward heaven, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: stop the repression!

There are questions I must keep asking myself, as I read Elle’s book and remember Romero: Where am I called to stand? What truth am I called to speak and to whom? Where does justice demand that I use my authority as a priest of the Church and my privilege as a white, middle class, educated person to speak out, as Romero did? And more importantly, perhaps, as Elle has been reminding me in her book, whose voices should I be listening to? Whose experiences need to guide my work? What are my blind spots? What is my complicity?

I’m still figuring that out.

And so today, I ask St. Oscar Romero to pray for me, that I may listen as he did, to the cry of the oppressed, and discern, as he did, how to act as the Gospel demands and as Jesus calls.

*And I’ll just say this here, because somehow it still needs to be said: torture is always wrong. It can irreparably change a person’s brain and body, leaving them with permanent scars, seen and unseen, and leaving others to live with the aftereffects. Having lived with a torture survivor, I can tell you that it is tedious, and taxing, and hellish, all at the same time.