A long time ago I heard a theology professor say, “You can’t talk about the Trinity without committing heresy. You just have to decide what is not negotiable and what heresy you can live with.” In her case, the Incarnation was not negotiable, so any Trinitarian statement that compromised God’s taking on human flesh was not to be tolerated.

Shortly before Trinity Sunday, you’ll hear the preachers whine and tear out their hair (not sure what that sounds like) trying to remain within some kind of orthodox boundaries while not putting their congregations to sleep.

I’ve not had that issue with preaching on Trinity Sunday. For one, my Trinitarian theology was profoundly shaped by Robert Farrar Capon’s delightful fantasy describing the Trinity’s calling forth of creation as an epic dinner party with bad jokes and crazy fish swimming in the glasses of wine. (See The Third Peacock, chapter 1, “Let Me Tell You Why.” You can read the excerpt here.)

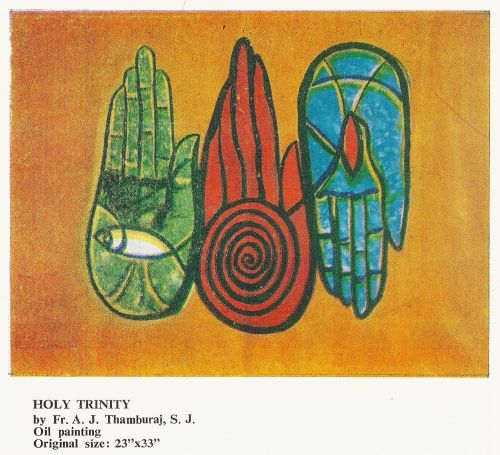

What I learned from Capon is that the Trinity is a party. Now much smarter and more erudite theologians will have more nuanced and complete ways of elucidating this (often using that very sexy word, “perichoresis,” which literally means “rotation” and actually makes the Trinity not just a party, but a dance party!).

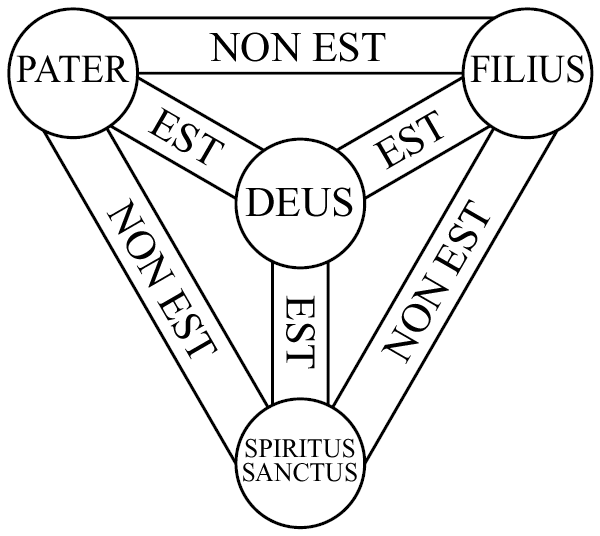

The upshot is that the Trinity is hard to grasp, both in terms of brute understanding and of overall comprehension: Three in One and One in Three? One God yet Three Persons? (Persons being not a simple cognate of the Latin persona.) Coequal, coeternal, consubstantial? In my former parish we used to recite the Athanasian Creed on Trinity Sunday—which includes this bit: “As also there are not three incomprehensibles, nor three uncreated: but one uncreated, and one incomprehensible,” to which one Trinity Sunday I quipped, “The whole d*mn thing incomprehensible.” It always struck me as defensive, defining God as what the Trinity is not, rather than what God is.

The Christian tradition from very early on—as early as Paul’s letters and the Gospels—had rudimentary Trinitarian formulations. As the theology of the Trinity developed over the centuries, there was this strange insistence on contradictory and paradoxical assertions1: three yet one, united in deity and action, yet distinguished by name and relationship to each other. We seemed, as our Jewish and Muslim cousins often point out, intent on making it stupid hard not to look like polytheists!

Years ago, when I was making the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, I had an experience in prayer of someone I thought was Jesus. He seemed a little judgier than usual, kind of sharp, which can happen, but something didn’t feel right. So I extrapolated that Jesus onto the Trinity: what would the Trinity be like if Jesus as I was experiencing Him now were the 2nd Person, i.e. the Son? When I did that it felt all wrong and it became clear that the Enemy2 was trying to distract me from the work God had in mind for me that day, prayer-wise.

So why this strange insistence on making the Trinity so difficult to grasp?

Judaism has, since day one, has taken a strong stand against idolatry, which essentially means allowing anything or anyone to take God’s place. Christianity inherited that insistence.3

So it has occurred to me that perhaps the Christian tangle of contradictions (we like to call them paradoxes or mysteries, but tomato, tomahto) that we have built up around the Trinity is a way of preventing a kind of idolatry: if you can’t pin down God as Trinity, then, well, you can’t pin down God!

I’ve found that when I pray with the Trinity (versus praying with the Father, the Son, or the Spirit), my experience of God is more expansive, a little darker (i.e. more mysterious), more dynamic, a bit like a stationary whirlwind. (Some of you may associate a more dynamic experience of God with the Holy Spirit, which I find to be the case, too. The Trinity feels more three dimensional, which as the Spirit is more two dimensional wind-like?)

Perhaps we should pray to and with the Trinity more often. This is God as ultimate, yet loving mystery. This is God way beyond gender. This is God who is, dare I say, syncopated, but something more complicated than a two-against-three rhythm (or this amazing 4-against-7 polyrhythm or this one, which I can’t break down at all).

This is the God who refuses to be boxed up or boxed in, the God is not even limited by the categories we have assigned to God. The infinite God who would learn finitude, the omnipotent God who seems to prefer to manifest itself in human frailty, the omnipresent God who chose life in a single time and place to redeem all of humanity.

So maybe we should relax about the Trinity. As long as we allow this three-way paradox, perhaps we’ll allow God to be God?

- Along with its sibling paradox, the dual nature of Christ, i.e. Christ is fully human and fully divine, completely and inseparably, yet without losing the qualities of either one. ↩︎

- A brilliant bit of vocabulary, which can mean Satan, an evil spirit, my neuroses, or the effects of a bad day, depending on your theology and what’s most useful in getting yourself back on track. ↩︎

- Pace my Hindu and Pagan and other polytheistic friends. I have no issue with multiple gods, nor with images made of them per se if that’s your religious jam. But among the monotheists, all three of the big ones—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—are pretty insistent on there being just one God and that our loyalties are not to be divided, and the Jews and Muslims particiularly clear—clearer, frankly, than the Christians are in practice—on not making images of the divine. ↩︎